An Introduction to Recurrent Neural Networks for Beginners

A simple walkthrough of what RNNs are, how they work, and how to build one from scratch in Python.

| UPDATED

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are a kind of neural network that specialize in processing sequences. They’re often used in Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks because of their effectiveness in handling text. In this post, we’ll explore what RNNs are, understand how they work, and build a real one from scratch (using only numpy) in Python.

This post assumes a basic knowledge of neural networks. My introduction to Neural Networks covers everything you’ll need to know, so I’d recommend reading that first.

Let’s get into it!

1. The Why

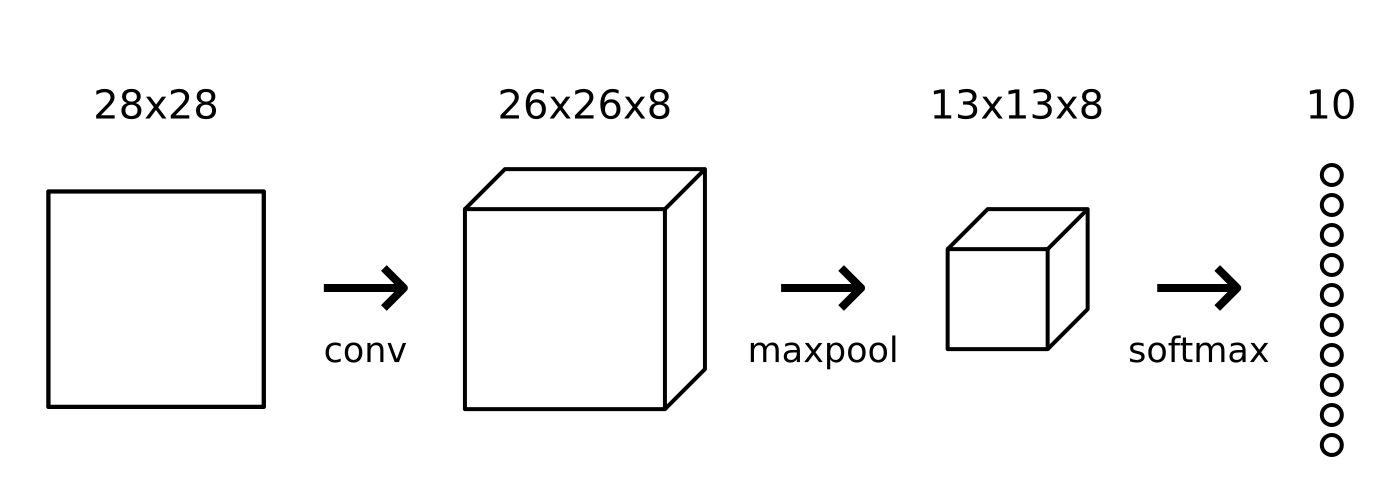

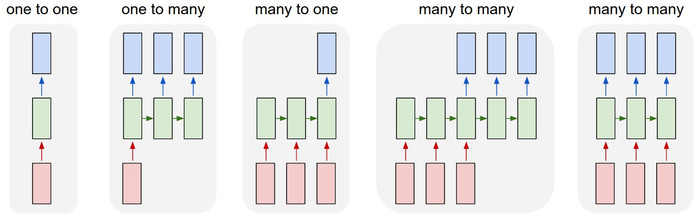

One issue with vanilla neural nets (and also CNNs) is that they only work with pre-determined sizes: they take fixed-size inputs and produce fixed-size outputs. RNNs are useful because they let us have variable-length sequences as both inputs and outputs. Here are a few examples of what RNNs can look like:

This ability to process sequences makes RNNs very useful. For example:

- Machine Translation (e.g. Google Translate) is done with “many to many” RNNs. The original text sequence is fed into an RNN, which then produces translated text as output.

- Sentiment Analysis (e.g. Is this a positive or negative review?) is often done with “many to one” RNNs. The text to be analyzed is fed into an RNN, which then produces a single output classification (e.g. This is a positive review).

Later in this post, we’ll build a “many to one” RNN from scratch to perform basic Sentiment Analysis.

2. The How

Let’s consider a “many to many” RNN with inputs that wants to produce outputs . These and are vectors and can have arbitrary dimensions.

RNNs work by iteratively updating a hidden state , which is a vector that can also have arbitrary dimension. At any given step ,

- The next hidden state is calculated using the previous hidden state and the next input .

- The next output is calculated using .

Here’s what makes a RNN recurrent: it uses the same weights for each step. More specifically, a typical vanilla RNN uses only 3 sets of weights to perform its calculations:

- , used for all → links.

- , used for all → links.

- , used for all → links.

We’ll also use two biases for our RNN:

- , added when calculating .

- , added when calculating .

We’ll represent the weights as matrices and the biases as vectors. These 3 weights and 2 biases make up the entire RNN!

Here are the equations that put everything together:

All the weights are applied using matrix multiplication, and the biases are added to the resulting products. We then use tanh as an activation function for the first equation (but other activations like sigmoid can also be used).

No idea what an activation function is? Read my introduction to Neural Networks like I mentioned. Seriously.

3. The Problem

Let’s get our hands dirty! We’ll implement an RNN from scratch to perform a simple Sentiment Analysis task: determining whether a given text string is positive or negative.

Here are a few samples from the small dataset I put together for this post:

| Text | Positive? |

|---|---|

| i am good | ✓ |

| i am bad | ❌ |

| this is very good | ✓ |

| this is not bad | ✓ |

| i am bad not good | ❌ |

| i am not at all happy | ❌ |

| this was good earlier | ✓ |

| i am not at all bad or sad right now | ✓ |

4. The Plan

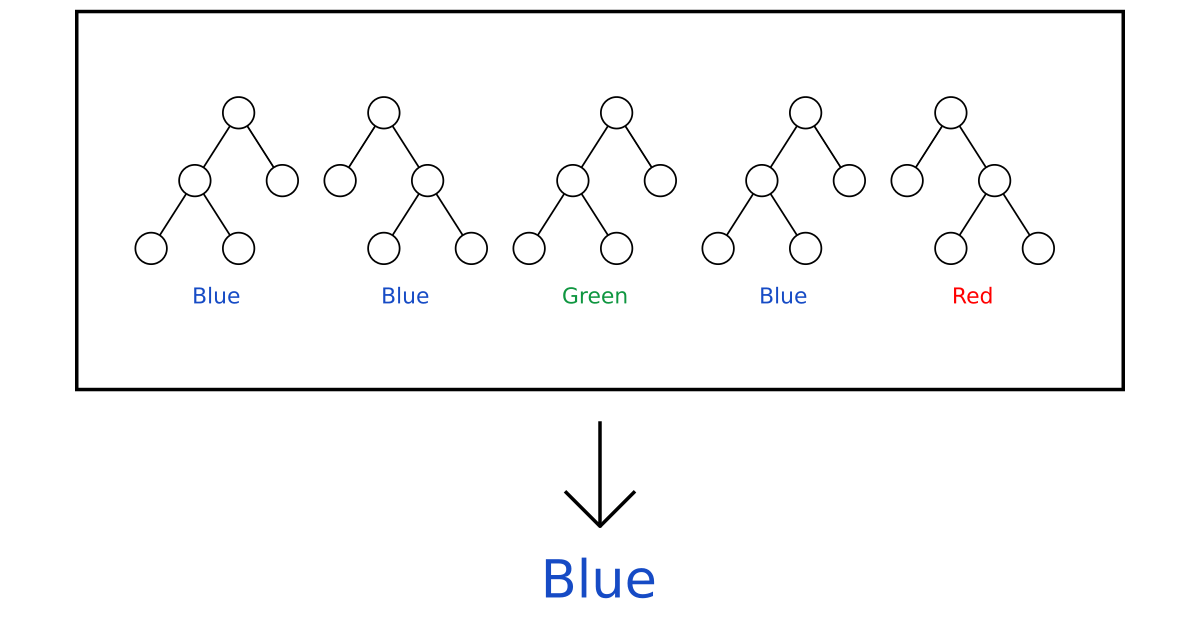

Since this is a classification problem, we’ll use a “many to one” RNN. This is similar to the “many to many” RNN we discussed earlier, but it only uses the final hidden state to produce the one output :

Each will be a vector representing a word from the text. The output will be a vector containing two numbers, one representing positive and the other negative. We’ll apply Softmax to turn those values into probabilities and ultimately decide between positive / negative.

Let’s start building our RNN!

5. The Pre-Processing

The dataset I mentioned earlier consists of two Python dictionaries:

data.py

train_data = {

'good': True,

'bad': False,

# ... more data

}

test_data = {

'this is happy': True,

'i am good': True,

# ... more data

}We’ll have to do some pre-processing to get the data into a usable format. To start, we’ll construct a vocabulary of all words that exist in our data:

main.py

from data import train_data, test_data

# Create the vocabulary.

vocab = list(set([w for text in train_data.keys() for w in text.split(' ')]))

vocab_size = len(vocab)

print('%d unique words found' % vocab_size) # 18 unique words foundvocab now holds a list of all words that appear in at least one training text. Next, we’ll assign an integer index to represent each word in our vocab.

main.py

# Assign indices to each word.

word_to_idx = { w: i for i, w in enumerate(vocab) }

idx_to_word = { i: w for i, w in enumerate(vocab) }

print(word_to_idx['good']) # 16 (this may change)

print(idx_to_word[0]) # sad (this may change)We can now represent any given word with its corresponding integer index! This is necessary because RNNs can’t understand words - we have to give them numbers.

Finally, recall that each input to our RNN is a vector. We’ll use one-hot vectors, which contain all zeros except for a single one. The “one” in each one-hot vector will be at the word’s corresponding integer index.

Since we have 18 unique words in our vocabulary, each will be a 18-dimensional one-hot vector.

main.py

import numpy as np

def createInputs(text):

'''

Returns an array of one-hot vectors representing the words

in the input text string.

- text is a string

- Each one-hot vector has shape (vocab_size, 1)

'''

inputs = []

for w in text.split(' '):

v = np.zeros((vocab_size, 1))

v[word_to_idx[w]] = 1

inputs.append(v)

return inputsWe’ll use createInputs() later to create vector inputs to pass in to our RNN.

6. The Forward Phase

It’s time to start implementing our RNN! We’ll start by initializing the 3 weights and 2 biases our RNN needs:

rnn.py

import numpy as np

from numpy.random import randn

class RNN:

# A Vanilla Recurrent Neural Network.

def __init__(self, input_size, output_size, hidden_size=64):

# Weights

self.Whh = randn(hidden_size, hidden_size) / 1000

self.Wxh = randn(hidden_size, input_size) / 1000

self.Why = randn(output_size, hidden_size) / 1000

# Biases

self.bh = np.zeros((hidden_size, 1))

self.by = np.zeros((output_size, 1))We use np.random.randn() to initialize our weights from the standard normal distribution.

Next, let’s implement our RNN’s forward pass. Remember these two equations we saw earlier?

Here are those same equations put into code:

rnn.py

class RNN:

# ...

def forward(self, inputs):

'''

Perform a forward pass of the RNN using the given inputs.

Returns the final output and hidden state.

- inputs is an array of one-hot vectors with shape (input_size, 1).

'''

h = np.zeros((self.Whh.shape[0], 1))

# Perform each step of the RNN

for i, x in enumerate(inputs):

h = np.tanh(self.Wxh @ x + self.Whh @ h + self.bh)

# Compute the output

y = self.Why @ h + self.by

return y, hPretty simple, right? Note that we initialized to the zero vector for the first step, since there’s no previous we can use at that point.

Let’s try it out:

main.py

# ...

def softmax(xs):

# Applies the Softmax Function to the input array.

return np.exp(xs) / sum(np.exp(xs))

# Initialize our RNN!

rnn = RNN(vocab_size, 2)

inputs = createInputs('i am very good')

out, h = rnn.forward(inputs)

probs = softmax(out)

print(probs) # [[0.50000095], [0.49999905]]Our RNN works, but it’s not very useful yet. Let’s change that…

Liking this introduction so far? Subscribe to my newsletter to get notified about new Machine Learning posts like this one.

7. The Backward Phase

In order to train our RNN, we first need a loss function. We’ll use cross-entropy loss, which is often paired with Softmax. Here’s how we calculate it:

where is our RNN’s predicted probability for the correct class (positive or negative). For example, if a positive text is predicted to be 90% positive by our RNN, the loss is:

Want a longer explanation? Read the Cross-Entropy Loss section of my introduction to Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs).

Now that we have a loss, we’ll train our RNN using gradient descent to minimize loss. That means it’s time to derive some gradients!

⚠️ The following section assumes a basic knowledge of multivariable calculus. You can skip it if you want, but I recommend giving it a skim even if you don’t understand much. We’ll incrementally write code as we derive results, and even a surface-level understanding can be helpful.

If you want some extra background for this section, I recommend first reading the Training a Neural Network section of my introduction to Neural Networks. Also, all of the code for this post is on Github, so you can follow along there if you’d like.

Ready? Here we go.

7.1 Definitions

First, some definitions:

- Let represent the raw outputs from our RNN.

- Let represent the final probabilities: .

- Let refer to the true label of a certain text sample, a.k.a. the “correct” class.

- Let be the cross-entropy loss: .

- Let , , and be the 3 weight matrices in our RNN.

- Let and be the 2 bias vectors in our RNN.

7.2 Setup

Next, we need to edit our forward phase to cache some data for use in the backward phase. While we’re at it, we’ll also setup the skeleton for our backwards phase. Here’s what that looks like:

rnn.py

class RNN:

# ...

def forward(self, inputs):

'''

Perform a forward pass of the RNN using the given inputs.

Returns the final output and hidden state.

- inputs is an array of one-hot vectors with shape (input_size, 1).

'''

h = np.zeros((self.Whh.shape[0], 1))

self.last_inputs = inputs self.last_hs = { 0: h }

# Perform each step of the RNN

for i, x in enumerate(inputs):

h = np.tanh(self.Wxh @ x + self.Whh @ h + self.bh)

self.last_hs[i + 1] = h

# Compute the output

y = self.Why @ h + self.by

return y, h

def backprop(self, d_y, learn_rate=2e-2): ''' Perform a backward pass of the RNN. - d_y (dL/dy) has shape (output_size, 1). - learn_rate is a float. ''' passCurious about why we’re doing this caching? Read my explanation in the Training Overview of my introduction to CNNs, in which we do the same thing.

7.3 Gradients

It’s math time! We’ll start by calculating . We know:

I’ll leave the actual derivation of using the Chain Rule as an exercise for you 😉, but the result comes out really nice:

For example, if we have and the correct class is , then we’d get . This is also quite easy to turn into code:

main.py

# Loop over each training example

for x, y in train_data.items():

inputs = createInputs(x)

target = int(y)

# Forward

out, _ = rnn.forward(inputs)

probs = softmax(out)

# Build dL/dy

d_L_d_y = probs d_L_d_y[target] -= 1

# Backward

rnn.backprop(d_L_d_y)Nice. Next up, let’s take a crack at gradients for and , which are only used to turn the final hidden state into the RNN’s output. We have:

where is the final hidden state. Thus,

Similarly,

We can now start implementing backprop()!

rnn.py

class RNN:

# ...

def backprop(self, d_y, learn_rate=2e-2):

'''

Perform a backward pass of the RNN.

- d_y (dL/dy) has shape (output_size, 1).

- learn_rate is a float.

'''

n = len(self.last_inputs)

# Calculate dL/dWhy and dL/dby.

d_Why = d_y @ self.last_hs[n].T d_by = d_yReminder: We created

self.last_hsinforward()earlier.

Finally, we need the gradients for , , and , which are used every step during the RNN. We have:

because changing affects every , which all affect and ultimately . In order to fully calculate the gradient of , we’ll need to backpropagate through all timesteps, which is known as Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT):

is used for all → forward links, so we have to backpropagate back to each of those links.

Once we arrive at a given step , we need to calculate :

The derivative of is well-known:

We use Chain Rule like usual:

Similarly,

The last thing we need is . We can calculate this recursively:

We’ll implement BPTT starting from the last hidden state and working backwards, so we’ll already have by the time we want to calculate ! The exception is the last hidden state, :

We now have everything we need to finally implement BPTT and finish backprop():

rnn.py

class RNN:

# ...

def backprop(self, d_y, learn_rate=2e-2):

'''

Perform a backward pass of the RNN.

- d_y (dL/dy) has shape (output_size, 1).

- learn_rate is a float.

'''

n = len(self.last_inputs)

# Calculate dL/dWhy and dL/dby.

d_Why = d_y @ self.last_hs[n].T

d_by = d_y

# Initialize dL/dWhh, dL/dWxh, and dL/dbh to zero.

d_Whh = np.zeros(self.Whh.shape)

d_Wxh = np.zeros(self.Wxh.shape)

d_bh = np.zeros(self.bh.shape)

# Calculate dL/dh for the last h.

d_h = self.Why.T @ d_y

# Backpropagate through time.

for t in reversed(range(n)):

# An intermediate value: dL/dh * (1 - h^2)

temp = ((1 - self.last_hs[t + 1] ** 2) * d_h)

# dL/db = dL/dh * (1 - h^2)

d_bh += temp

# dL/dWhh = dL/dh * (1 - h^2) * h_{t-1}

d_Whh += temp @ self.last_hs[t].T

# dL/dWxh = dL/dh * (1 - h^2) * x

d_Wxh += temp @ self.last_inputs[t].T

# Next dL/dh = dL/dh * (1 - h^2) * Whh

d_h = self.Whh @ temp

# Clip to prevent exploding gradients.

for d in [d_Wxh, d_Whh, d_Why, d_bh, d_by]:

np.clip(d, -1, 1, out=d)

# Update weights and biases using gradient descent.

self.Whh -= learn_rate * d_Whh

self.Wxh -= learn_rate * d_Wxh

self.Why -= learn_rate * d_Why

self.bh -= learn_rate * d_bh

self.by -= learn_rate * d_byA few things to note:

- We’ve merged into for convenience.

- We’re constantly updating a

d_hvariable that holds the most recent , which we need to calculate . - After finishing BPTT, we np.clip() gradient values that are below -1 or above 1. This helps mitigate the exploding gradient problem, which is when gradients become very large due to having lots of multiplied terms. Exploding or vanishing gradients are quite problematic for vanilla RNNs - more complex RNNs like LSTMs are generally better-equipped to handle them.

- Once all gradients are calculated, we update weights and biases using gradient descent.

We’ve done it! Our RNN is complete.

8. The Culmination

It’s finally the moment we been waiting for - let’s test our RNN!

First, we’ll write a helper function to process data with our RNN:

main.py

import random

def processData(data, backprop=True):

'''

Returns the RNN's loss and accuracy for the given data.

- data is a dictionary mapping text to True or False.

- backprop determines if the backward phase should be run.

'''

items = list(data.items())

random.shuffle(items)

loss = 0

num_correct = 0

for x, y in items:

inputs = createInputs(x)

target = int(y)

# Forward

out, _ = rnn.forward(inputs)

probs = softmax(out)

# Calculate loss / accuracy

loss -= np.log(probs[target])

num_correct += int(np.argmax(probs) == target)

if backprop:

# Build dL/dy

d_L_d_y = probs

d_L_d_y[target] -= 1

# Backward

rnn.backprop(d_L_d_y)

return loss / len(data), num_correct / len(data)Now, we can write the training loop:

main.py

# Training loop

for epoch in range(1000):

train_loss, train_acc = processData(train_data)

if epoch % 100 == 99:

print('--- Epoch %d' % (epoch + 1))

print('Train:\tLoss %.3f | Accuracy: %.3f' % (train_loss, train_acc))

test_loss, test_acc = processData(test_data, backprop=False)

print('Test:\tLoss %.3f | Accuracy: %.3f' % (test_loss, test_acc))Running main.py should output something like this:

--- Epoch 100

Train: Loss 0.688 | Accuracy: 0.517

Test: Loss 0.700 | Accuracy: 0.500

--- Epoch 200

Train: Loss 0.680 | Accuracy: 0.552

Test: Loss 0.717 | Accuracy: 0.450

--- Epoch 300

Train: Loss 0.593 | Accuracy: 0.655

Test: Loss 0.657 | Accuracy: 0.650

--- Epoch 400

Train: Loss 0.401 | Accuracy: 0.810

Test: Loss 0.689 | Accuracy: 0.650

--- Epoch 500

Train: Loss 0.312 | Accuracy: 0.862

Test: Loss 0.693 | Accuracy: 0.550

--- Epoch 600

Train: Loss 0.148 | Accuracy: 0.914

Test: Loss 0.404 | Accuracy: 0.800

--- Epoch 700

Train: Loss 0.008 | Accuracy: 1.000

Test: Loss 0.016 | Accuracy: 1.000

--- Epoch 800

Train: Loss 0.004 | Accuracy: 1.000

Test: Loss 0.007 | Accuracy: 1.000

--- Epoch 900

Train: Loss 0.002 | Accuracy: 1.000

Test: Loss 0.004 | Accuracy: 1.000

--- Epoch 1000

Train: Loss 0.002 | Accuracy: 1.000

Test: Loss 0.003 | Accuracy: 1.000Not bad from a RNN we built ourselves. 💯

Want to try or tinker with this code yourself? Run this RNN in your browser. It’s also available on Github.

9. The End

That’s it! In this post, we completed a walkthrough of Recurrent Neural Networks, including what they are, how they work, why they’re useful, how to train them, and how to implement one. There’s still much more you can do, though:

- Learn about Long short-term memory networks, a more powerful and popular RNN architecture, or about Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), a well-known variation of the LSTM.

- Experiment with bigger / better RNNs using proper ML libraries like Tensorflow, Keras, or PyTorch.

- Read the rest of my Neural Networks from Scratch series.

- Read about Bidirectional RNNs, which process sequences both forwards and backwards so more information is available to the output layer.

- Try out Word Embeddings like GloVe or Word2Vec, which can be used to turn words into more useful vector representations.

- Check out the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK), a popular Python library for working with human language data.

I write a lot about Machine Learning, so subscribe to my newsletter if you’re interested in getting future ML content from me.

Thanks for reading!